KENORA — “Hey bro, I’m checking out of here tomorrow. Pissed off. Just let the other bro know,” 57-year-old Bruce Frogg texted his oldest brother Joshua on June 20, 2024 from a halfway house in Kenora. “I’m just gonna clear it with p.o. (parole officer). I’m free already. For two weeks already. So I’m packing tonight. I’ll let you know tomorrow where I’ll be at.”

Five days later, Bruce doused the ice cream shop in Anicinabe Park with gasoline and set it on fire while brandishing machetes. A responding OPP officer shot him dead with three bullets from a rifle.

“Something must have transpired,” Joshua said. “He was on track and all of a sudden… it didn’t make sense. It didn’t make sense.”

All accounts were that Bruce had been sober and getting better in Kenora.

The hunter and trapper from the fly-in community of Wawakapewin First Nation, who had spent much of his life in Wapekeka First Nation, was enrolled in programs and finally getting the help he needed. Frogg had struggled with alcohol, agitated by a harrowing childhood of loss, physical and sexual abuse.

Joshua was waiting on word to pick his brother up. On the same day Bruce texted him, he also phoned his daughter Esther in Wunnumin Lake First Nation and told her he was looking forward to coming home and seeing his grandchildren.

Joshua has been on leave from his job as Wapekeka’s band manager for a year since the shooting. One of Bruce’s daughters died of overdose, weeks after his death.

But as unexpected as Bruce’s extra-judicial killing had been and as hard as life has been since, the family was equally shocked when a report from Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit director was published this week, clearing the officers involved.

Twenty-two minutes passed between noon that day, when Bruce set fire to the building and an adjacent firewood cart “in a highly agitated state,” and the gunfire that killed him.

Water from a firehose struck him indirectly and according to the SIU report, he then “removed his shirt, walked off the deck down a ramp onto the parking lot. He took three steps in the parking lot in the direction of the firefighters and group of officers including SO #2, when the officer fired three times.”

“I don’t know if that was the right call,” the officer said breathing heavily and sitting down in his cruiser, a minute after he shot Bruce.

SIU director Joseph Martino found that officer, “reasonably believed he had no choice but to shoot him,” while he cited concern for Bruce’s safety standing near the burning building to clear the negotiator, whose choices, “did not amount to a marked and substantial departure from a reasonable standard of care in the circumstances.”

Martino’s report also ruled out non-lethal alternatives. The Emergency Response Team happened to be training elsewhere with the Kenora OPP’s non-lethal projectile weapons, the flammable fluid disqualified the use of Conductive Energy Weapons (better known as Tasers), and he agreed with OPP’s choice against deploying the police dog, fearing it might chase Bruce back into the fire.

The SIU declined an interview for this story.

More questions

The SIU’s Indigenous representative delivered the report to Bruce’s family at Nishnawbe Aski Nation’s office in Thunder Bay on June 27. Joshua said the representative had no answers beyond the report’s contents.

“The justification they had was that he committed arson and he had weapons. That’s it,” Joshua said. “It’s beyond my comprehension for that to justify that use of deadly force.”

As a hunter familiar with rifle use, Joshua asked, why three shots in the chest and abdomen? How was the officer who shot Bruce justified in feeling threatened when there were four officers with guns trained on him and only one fired? How was anyone threatened when they were standing so far away? How did an armed standoff that Kenora OPP attended only weeks earlier with a man who was armed end without gunfire but this one went differently?

Joshua couldn’t believe the toxicological report that showed Bruce had used crystal methamphetamine. So far as he knew, Bruce had never done a harder drug than marijuana.

And while the officers exercised their right not to speak to SIU, Joshua insisted his brother had a right to life.

“Anytime there’s a police shooting, there has to be an inquest. That’s the next thing,” he said. “We need to know why he was shot. They said they’d exhausted all the options. For me, it was a quick projection and he was executed. That’s how I feel.”

Nishnawbe Aski Nation, the advocacy group representing the chiefs of 49 First Nations in far northern Ontario including Wawakapewin and Wapekeka, issued a press release on Wednesday, rejecting the SIU’s findings.

“We are familiar with the SIU investigative process and do not see how this report could properly answer the question of whether an officer made “the right call.” We do not accept the SIU’s explanation of the circumstances that led to this officer taking Bruce’s life, and so we reject the conclusion that the officers’ actions were reasonable and justified,” the statement from NAN Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler reads.

“We believe the SIU’s investigation has raised more questions than answers, and that this process is severely flawed. We are working closely with the family and community to explore other avenues for justice.”

Bruce’s daughter Esther said NAN’s sentiment echoes her family’s passion and resolve for justice.

“I want whoever did this thing to be held accountable. This is unfair what happened to him,” Esther said. “We’ve agreed unanimously and collectively as a family that we are not going to let this go.”

She echoed NAN’s frustration that the SIU report failed to take systemic factors into account, including Bruce’s history.

Young Trauma

When Bruce was 5 years old, his oldest brother drowned falling through the ice on a snow machine. He lost another brother to overdose, a third to suicide. He had permanent injuries and skull deformities from the beatings his father laid on him, which he interpreted as the legacy of residential school. He and three other boys would hold sleepovers at each other’s homes to stay safe. When they were living in KI, Joshua would show up in Wapakeka bruised and barely walking.

In a 2005 interview with this reporter, Bruce said he was sexually abused as a boy by Ralph Rowe, who Wawatay News has called “Canada’s most prolific pedophile.” The Anglican priest and scoutmaster who travelled to fly-in First Nations by float plane in the 1970s and 1980s is believed to have sexually abused as many as 500 boys across northern Ontario and Manitoba.

Bruce recalled how every night, Rowe would take a different child into his tent. Adults didn’t believe those children who tried to speak up because the accusations were being made against a man of God. By Bruce’s count, at least thirteen of his scout troop members took their own lives.

Remembered on the land

From a young age, Bruce showed an uncanny proclivity for hunting, trapping, and tracking. He was widely known as “the professional” for his bush skills. He became legendary at nine years old for shooting his first moose — an accomplishment not only at his young age, but because he did it with a .22, a calibre of rifle usually reserved for hunting rabbits and other small game.

That’s how Esther will remember her father: on the land. Despite Bruce having spent the 1980s and early 1990s in and out of jail, and then the mid 2000s onward back and forth on the streets of Thunder Bay to the north, she said he was always there for his family. Her earliest memories involve Bruce taking her out on the land to teach her everything he knew.

“For me personally, he was a loving father. He raised me with strong morals. He raised me to be a strong woman,” she said.

“He was a good person, a loving person, always ready to help, help in any way he can. He was an avid outdoorsman. He loved his land. He loved his people. And that’s how I want people to know him.”

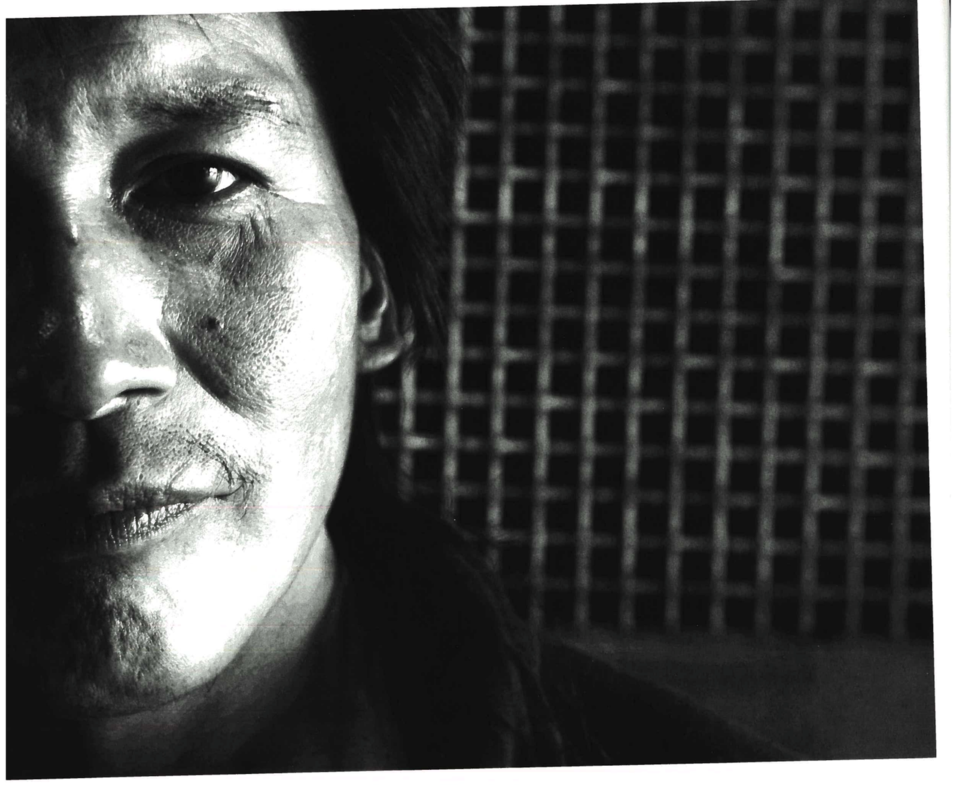

With notes from The Homelessness Project, a self-published 2007 book by Jon Thompson and photojournalist Jamie Smith about the ecosystem of extreme poverty in Thunder Bay. That book included a profile of Bruce Frogg.

Ricochet / Local Journalism Initiative